I have not had a particularly good blogging month – I seem to be saying that every month this year. I keep promising myself that I will write more reviews and then failing to do so. Blogging aside, I have enjoyed this month of reading. I don’t seem to be increasing the amount I read, but I’m really not bothered about that any more. I read some thoroughly immersive and compelling books this month.So, I would like to try and give a little flavour of all those books I have failed to review below.

It was only last month that I read the third Richard Osman book. My virtual WI bok group had chosen to read The Last Devil to Die (2023) by Richard Osman, his fourth in the successful Thursday Murder Club series, so I found myself returning to these characters sooner than I might otherwise have done. It was the only book I read on Kindle this month too. This novel continues several of the threads from the previous books, including the relationships of the two police officers and the story of Elizabeth’s husband Stephen – who is suffering some form of dementia. This is definitely the best book of the four – written with real warmth, it is surprisingly poignant, with a clear sense of everyone getting older, things changing and moving on. I believe Osman is taking a break from this series to concentrate on a new series, and this does seem to be a good place to leave everyone.

I heard about the novel Twice Lost (1960) by Phyllis Paul on another blog – and immediately bought a copy. Phyllis Paul is an English novelist who seems largely forgotten now despite having published a number of works between 1933 and 1967. Twice Lost is a slow burn, not a particularly quick read, I have seen it likened to The Turn of the Screw and Picnic at Hanging Rock, well I haven’t read the second of those, and I don’t really think it’s as dark as The Turn of the Screw. A child, Vivian Lambert disappears after a tennis party on a lovely summer day in an English village. Teengaer, Christine Grey is the last person to see Vivian, and is haunted by her disappearance for years after. Then, someone claiming to be the grown up Vivian appears and the mystery only deepens. Phyllis Paul makes the child Vivian unsympathetic, and the relationships between all the other characters are strange and dysfunctional. It’s a strange, unsettling novel, with a stifling, claustrophobic atmosphere.

Following on from that, Clothes-Pegs (1939) by Susan Scarlett reissued by Dean Street Press was a much lighter read. Annabel takes a job at a high end dressmaker’s in the sewing room, but is unexpectedly promoted to the role of ‘mannequin’ showing off the fine clothes to wealthy customers. Poor Annabel has to endure the cattiness of her fellow models, and when she catches the eye of Lord David de Bett she also unleashes the fury of the Honourable Octavia Glaye who has her own eye on David. A sweet comfort read, that reminded me a lot of Susan Scarlett’s Babbacombe’s – there’s a familiarity in the set up – but I enjoyed it nonetheless.

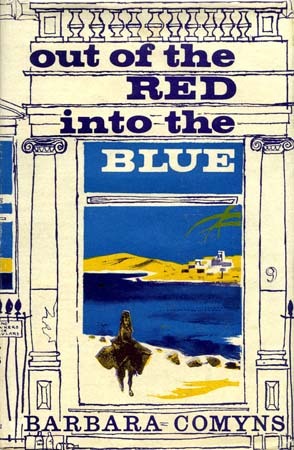

As I wanted to start the Comyns biography on my birthday, and I had finished Clothes-Pegs the afternoon before, I had to find something short for bedtime. On the Pottlecombe Cornice by (1908) Howard Sturgis fitted the bill. A tiny hardback novella from Michael Walmer. It’s really just a short story. Major Hankisson has retired to a little fishing village where a lovely new stretch of white road goes across the brow of the hill. Here is where the Major chooses to go walking, every day he sees a beautiful older woman, with whom he doesn’t speak, but enjoys seeing each day. He decides to find out what he can about her.

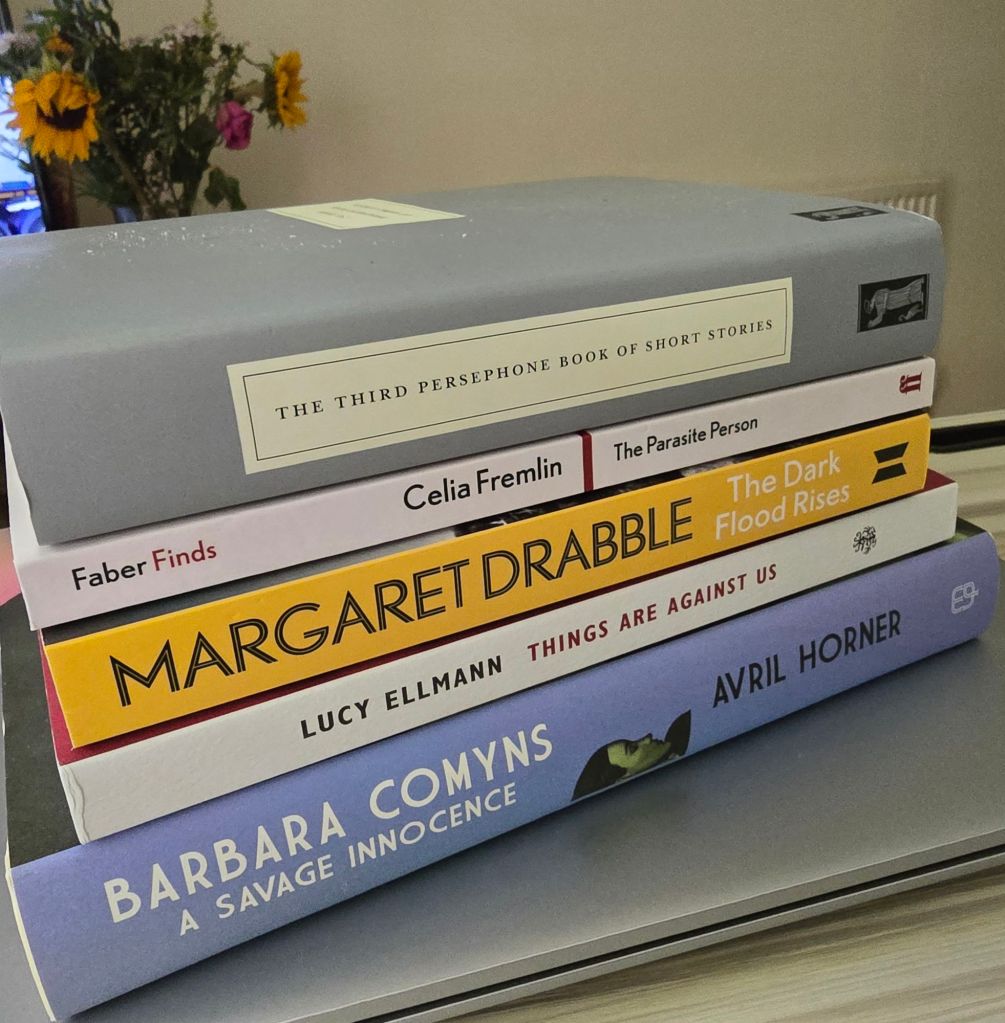

Long anticipated, and bought for me by Liz for my birthday Barbara Comyns – Savage Innocence (2024) by Avril Horner is the only book read in May that I have also reviewed, so I won’t repeat myself here. It was easily my book of the month.

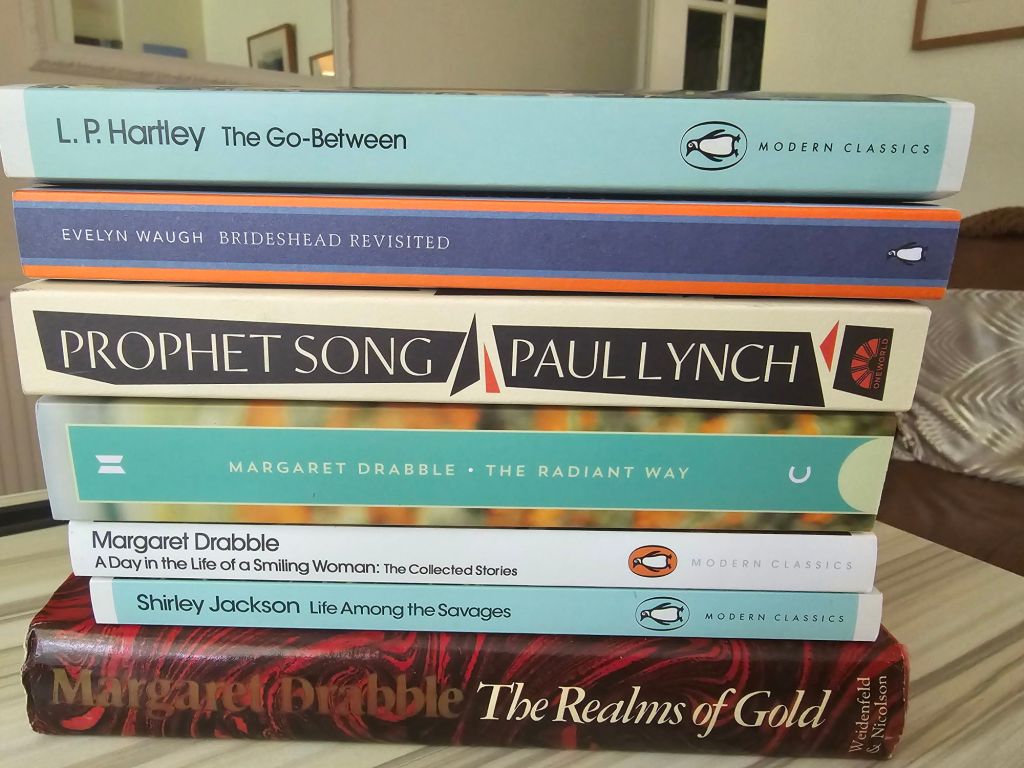

With The Realms of Gold (1975) by Margaret Drabble I continued my Drabble reading. Another brilliant read, a complex, intelligently written immersive novel, quite a slow read, but one I loved spending time with. Frances Wingate is a successful archeologist, divorced with children, she has recently separated from her married lover Karel – despite knowing she loves him. The novel opens as Frances is abroad to deliver a lecture at a conference. Later she travels to an African country for a similar event. She ruminates on her time with Karel – willing him to come back to her. Meanwhile we get a glimpse of some of her unknown relatives in the East Midlands. Naturally all the strands come together in a novel about family, civilisations, rituals and landscape. I think this is the longest of the Drabble novels I have read so far and It’s a shame that this novel remains out of print. I’m considering reading some of her short stories in June.

One of the books I bought recently was calling to me from the tbr; Life Among the Savages (1953) by Shirley Jackson is a memoir of family life. It is quite simply a delight. The memoir opens as Shirley and her husband and their two eldest children move to an old house in Vermont. Jackson’s account is very funny, as she manages misbehaving children, domestic mayhem and a rather oblivious husband. Her children (two more will be born) are imaginative and quite exhausting just to read about. There are imaginary friends, two cats and a dog to add into the equation – it’s glorious. Happily there is a sequel called Raising Demons, which I have also now ordered.

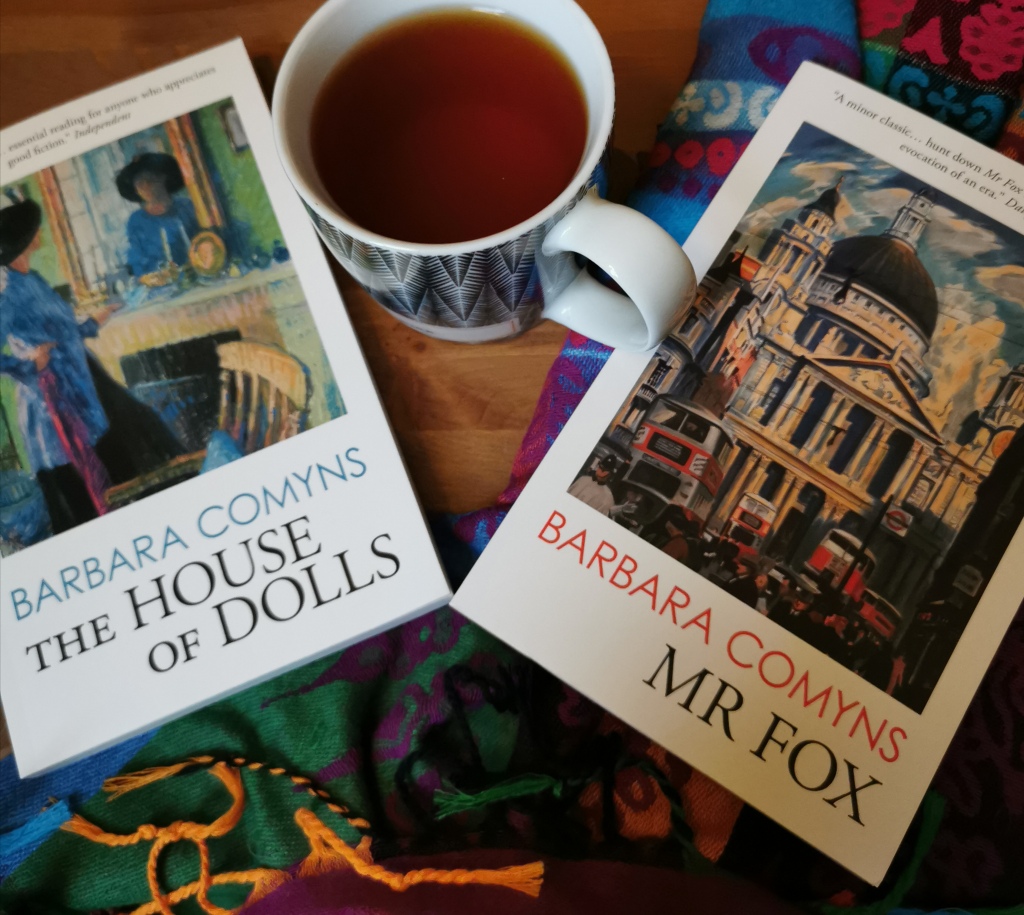

Well it was only a matter of time before I re-read Who was Changed and Who was Dead (1954) by Barbara Comyns. I re-read Our Spoons Came from Woolworths last year – and I had promised I would re-read the rest of Comyn’s novels. Reading that wonderful biography has just spurred me on. It is a famously strange and macabre novel, the river floods, ducks swim through the drawing room, then villagers go mad, some of them dying rather gruesomely. It is also rather brilliant. Surely a novel that could only have been written by Barbara Comyns.

So that’s it. I am contemplating a couple of book group reads at the moment. My feminist book group will be reading Spare Room by Helen Garner – I read it years ago, but a re-read will be required, so will be buying a new copy. My virtual WI book group is going to be reading The Sealwoman’s Gift by Sally Magnusson, which I can’t quite decide whether I want to read or not, so I haven’t bought that yet either. I have decided I will probably read a collection of Margaret Drabble’s short stories in June, and I have also decided to read the books I have now rather than keep reading chronologically and buying new ones. Having decided that it’s quite likely I won’t stick to it. Everything else will be decided by my mood.

What have you been reading in May? and what are you looking forward to next?

The household reminded me of the Mitfords, though maybe the Mitfords were less dysfunctional. There are unattractive aunts, a messy grandmother whose bedroom smelt of vinegar. None of the adults seem to have much going for them. The elder sister Mary bullies the other sisters badly and Barbara grows up closest to her sister Beatrix. Childhood ends as it must, crashing to a sudden halt when tragedy strikes.

The household reminded me of the Mitfords, though maybe the Mitfords were less dysfunctional. There are unattractive aunts, a messy grandmother whose bedroom smelt of vinegar. None of the adults seem to have much going for them. The elder sister Mary bullies the other sisters badly and Barbara grows up closest to her sister Beatrix. Childhood ends as it must, crashing to a sudden halt when tragedy strikes.