Sometime around this time last year I came up with the idea of a yearlong read-a-long of Virginia Woolf. Suddenly it is very nearly over.

“what is this moment of time, this particular day in which I have found

myself caught? The growl of traffic might be any uproar – forest trees or

the roar of wild beasts. Time has whizzed back an inch or two on its reel;

our short progress has been cancelled. I think also that our bodies are in truth

naked. We are only lightly covered with buttoned cloth; and beneath these

pavements are shells, bones and silence.”(Virginia Woolf – The Waves)

Our final phase of #Woolfalong was to read one or more of the novels: Jacob’s Room, The Waves and The Years. Originally – and perhaps optimistically, I intended to read all three – and I haven’t managed that. I read Jacob’s Room and The Waves, enjoying them both, but although I do have a few days of the year left, The Years must wait.

Fewer people managed to join in this phase – but I’m not surprised at that, the end of the year is always so busy. Still as ever I like to take a look at what other people read for phase 6.

#Woolfalong has enabled me to connect with non-blogging Woolf readers on Twitter. For phase 6. Mary, Adeline and Kate read The Waves, Anne read Jacob’s Room.

Caroline – from Bookword read and reviewed The Waves, which she admits to not having enjoyed as much as she had hoped. Liz from Adventures in reading, writing and working from home, read The Waves too, which Liz says in part is a critique on gender rolls (I hadn’t thought of this while I read it, but of course it is).

Karen from Kaggsysbookishramblings re-read Jacob’s Room after a gap of more than thirty years. Her reaction to reading Jacob’s Room was enormously positive, and she considers Jacob’s Room a good book for someone to begin their Woolf reading.

O from Beholdthestars read The Years which she describes as being measured by the changing seasons, her review makes me want to read it at some point in 2017.

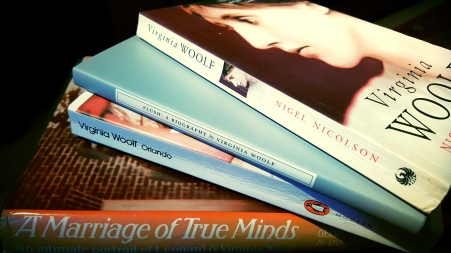

So, that’s it – #Woolfalong has taken rather more energy than I realised, but I am so very glad I did it, and so happy that so many lovely readers and bloggers joined in. I will continue reading Virginia Woolf, there are essays I still haven’t read, some short stories and The Years. I also have a books called The Marriage of True Minds about the relationship between Leonard and Virginia Woolf. On balance, I’m rather glad I haven’t read everything yet.

Last year, before embarking on #Woolfalong I read Orlando, The Voyage Out and A Room of One’s Own. It was those books which got me started, I had previously read To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway though many years earlier, and knew I needed to re-visit them first. #Woolfalong was born, so to speak, and since then I have read a lot more by and about Virginia Woolf. It’s been a wonderful experience, and I have gained so much by reading these books. There was no one else quite like her, and while I encountered some challenges along the way, they were welcome ones.

My favourites: To the Lighthouse, Night and Day, Flush, A writer’s Diary. Though for those of you who might be interested, below is a list of titles with links to all my #Woolfalong reviews.

Finally, I want to say a big thank you to everyone who has supported #Woolfalong – including Oxford World’s Classics – who back at the beginning of the year sent me a lovely box of Virginia Woolf books, some for me some for a giveaway. Also to Vintage books who provided books for a giveaway last December. Whether you’ve joined in all year – or once or twice along the way I was happy to have your company and your contributions, those who have retweeted, or posted comments on blog posts – your support is just as appreciated.

#Woolfalong reviews

To the Lighthouse

Mrs Dalloway

Night and Day

Between the Acts

Monday or Tuesday

Mrs Dalloway’s Party

Flush

Three Guineas

A Writer’s Diary

Jacob’s Room

The Waves

Virginia Woolf – Nigel Nicolson

Virginia Woolf; a critical memoir by Winifred Holtby

Recollections of Virginia Woolf -ed Joan Russell

Woolf’s non-fiction was the theme for phase 5. Virginia Woolf wrote an enormous number of essays, her two most famous A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas. Many more essays available in her famous two volumes of The Common Reader, there are now of course, other collections of her essays available like the selected essays from Oxford World classics which I bought but have still not read.

Woolf’s non-fiction was the theme for phase 5. Virginia Woolf wrote an enormous number of essays, her two most famous A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas. Many more essays available in her famous two volumes of The Common Reader, there are now of course, other collections of her essays available like the selected essays from Oxford World classics which I bought but have still not read.

The choices for readers was quite varied. Two Woolf novels – although called biographies by Woolf are of course Orlando and Flush. I read Orlando last year for a book group I was then attending. It was that book really, which set me off on my quest to know Virginia Woolf better, read much more of her work, and learn to appreciate her brilliance. #Woolfalong has done all of that for me, although I still feel something of a beginner with Woolf – even having read a few more books and with only two phases of #Woolfalong to go. So I opted to read

The choices for readers was quite varied. Two Woolf novels – although called biographies by Woolf are of course Orlando and Flush. I read Orlando last year for a book group I was then attending. It was that book really, which set me off on my quest to know Virginia Woolf better, read much more of her work, and learn to appreciate her brilliance. #Woolfalong has done all of that for me, although I still feel something of a beginner with Woolf – even having read a few more books and with only two phases of #Woolfalong to go. So I opted to read

Nigel Nicolson was the younger son of Vita Sackville West who was Virginia Woolf’s long-time friend and lover. During his childhood Virginia Woolf was a frequent visitor to the Nicolson family home, and it is Nigel Nicolson’s reminiscences of these childhood encounters that make this such a little gem. This edition also includes some wonderful photographs.

Nigel Nicolson was the younger son of Vita Sackville West who was Virginia Woolf’s long-time friend and lover. During his childhood Virginia Woolf was a frequent visitor to the Nicolson family home, and it is Nigel Nicolson’s reminiscences of these childhood encounters that make this such a little gem. This edition also includes some wonderful photographs.